Kenties kaikkien aikojen vaikutusvaltaisin kenttä- ja seikkailusuunnittelija Jennell Jaquays (syntyi Paul Jaquaysina vuonna 1956) menehtyi pitkällisen sairauden jälkeen vuoden alussa. Jennellin parhaiten muistetut työt lienevät alkuaikojen vaikutusvaltaiset Judges Guild -seikkailut Caverns of Thracia (1979) ja Dark Tower (1980), mutta hän ehti toimia elämänsä aikana paitsi roolipelien, myös tietokonepelien kenttäsuunnittelun parissa.

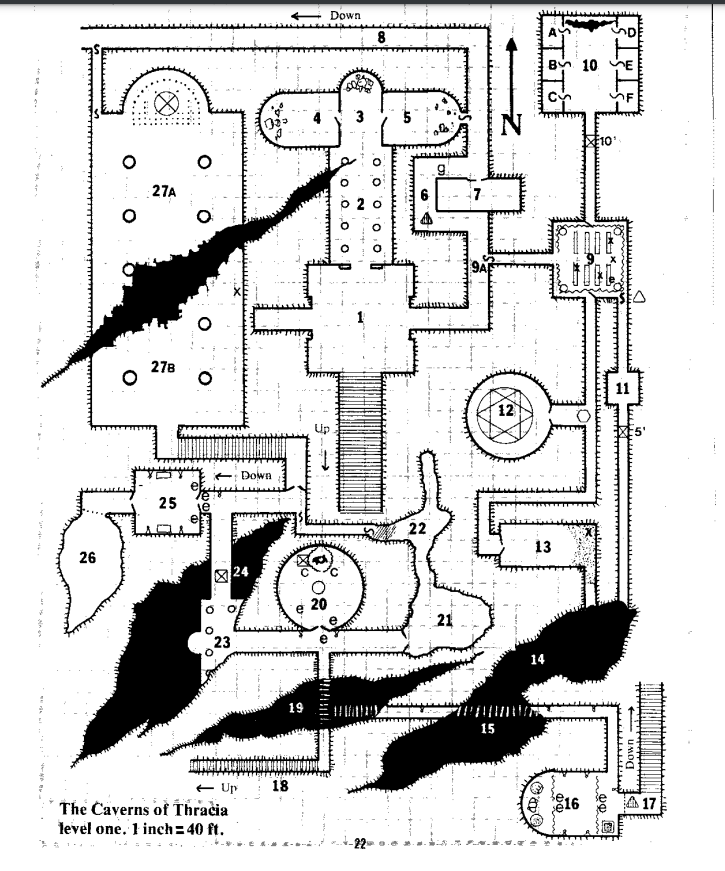

Jennell oli oikeastaan ensimmäisiä, jotka oivalsivat että onnistuneessa roolipeliseikkailussa pitää olla erilaisia tasoja. Se tarkoittaa historiallisia kerrostumia, mutta myös (ja ehkä ennen kaikkea) maantieteellisiä tasoja, ja tilaa liikkua niiden välillä Se tarkoittaa paitsi kenttiin piilotettuja salaisuuksia, myös pelaajille useita eri ratkaisuja tarjoavia luuppeja tai silmukoita. Jennellin karttasuunnittelun vaikuttavuudesta todistaa hänen nimestään väännetty verbi Jaquaysing, joka tarkoittaa kartan tai seikkailun monimutkaistamista niin, että sen voi läpäistä monien mahdollisuuksien ja reittien kautta.

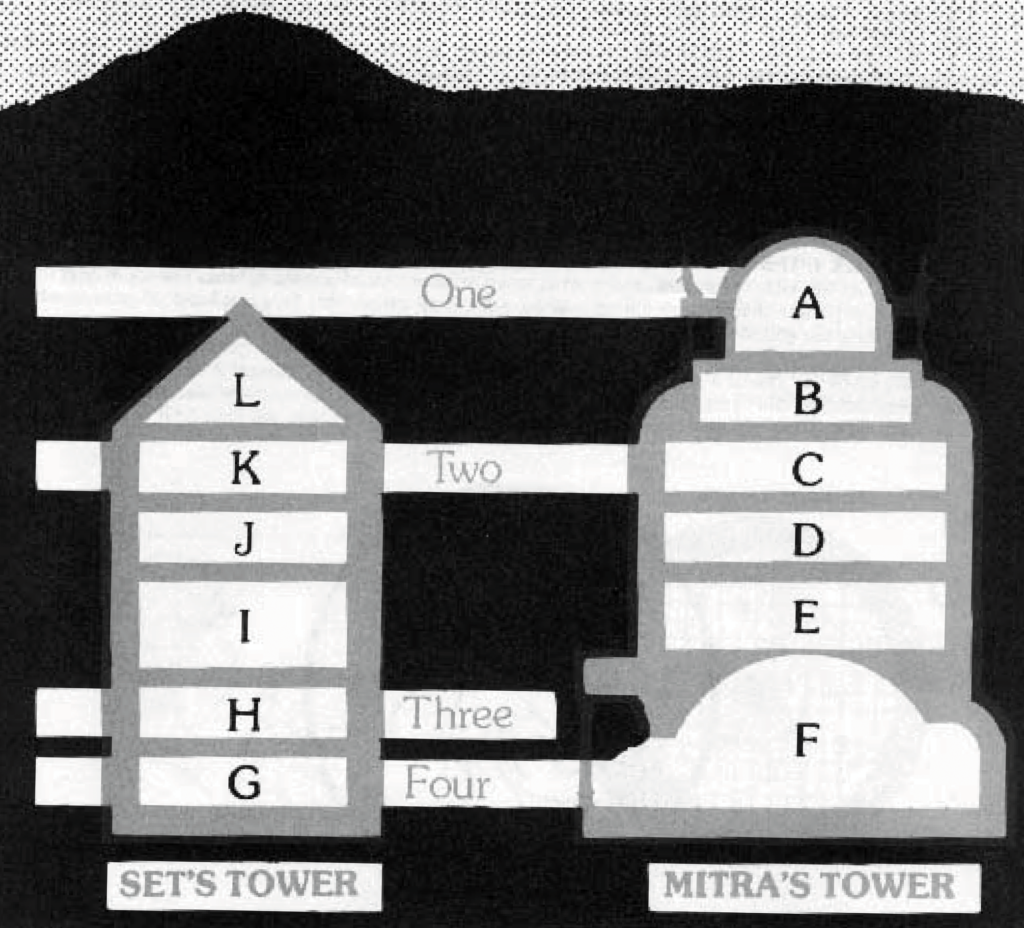

Jennellin luontaisesta kyvystä kehittää moniulotteisia ja sitä kautta kiehtovia seikkailuita ja karttoja kertoo jo 1970-luvun puolivälin Dungeoneer-julkaisu F’Chelrak’s Tomb (1976), joka kuuluu ylipäänsä ensimmäisten julkaistujen roolipeliseikkailujen joukkoon. Samanlaiset ominaisuudet kuvaavat myös Jennellin myöhempiä suunnittelutöitä, joihin kuuluu yllä mainitut Judges Guild -seikkailut, myös töitä RuneQuestin ja Central Castingin, sekä lukuisten eri tietokonealustojen parissa.

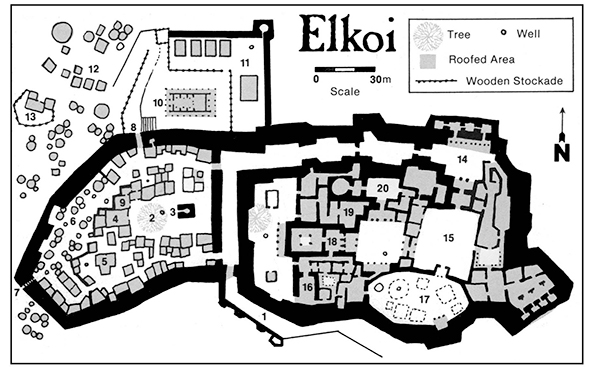

Suomessa Jennell Jaquays muistetaan kenties parhaiten Ace-pelien julkaisemasta Aarnikotkien saaresta (1989) (alkup. Griffin Island, 1986). Kyseessä on aikaisemman seikkailun Griffin Mountainin (1981) laajennoksesta, jossa seikkaillaan usean eri faktion hallitsemalla saarella. Seikkailu tekee paljon (ellei jopa kaiken) oikein, sillä mukana on paitsi kuvauksia saaren eri lokaatioista, myös paljon kiinnostavia NPC:tä, taikaesineitä, huhuja ja seikkailun tavoitteisiin liittyvää taustaa ja muuta tilpehööriä. Kaikki tämä on kuorrutettu upeilla kartoilla ja taiteella, niin että pelattavaa riittää kymmeniksi tunneiksi.

Vähemmän tunnettua on Jennellin työ tietokonepelien parissa, jossa hän ehti toimia paitsi varhaisten konsolikäännösten parissa, myös kenttäsuunnittelijana myöhemmissä Quake-peleissä, sekä taiteilijana ja pelisuunnittelijana mm. Age of Empire III:ssa ja Halo Warsissa. Tällainen kirjoitus Jennellistä jäi mieleen yhdestä Facebook-ryhmästä hänen kuolemansa aikoihin, joten liitetään se tänne loppuun:

I once cold messaged her with questions about dungeon design because I was preparing a workshop at my FLGS, this was her reply:

Hi Arjen:

My history in making games and game adventures goes back to my childhood.

My inspiration came from building worlds with blocks and playing out elaborate stories with small plastic figures, usually with my younger brother. And then of course, there were the board games we designed as kids, and worlds we created for our toys by gluing sheets of copy paper (used, printed side down) edge to edge and then drawing cities and secret lairs on them for our toys to explore.

My inspirational source material came from comic books of the 60s and 70s, stories of Greek, Norse, and Egyptian Mythology, legends of King Arthur and Robin Hood, early fantasy fiction like the Lord of the Rings, Fafhrd & Gray Mouser, Conan the Barbarian (and other REH heroes), Elric of Melnibone, and of course, John Carter of Mars and Carson of Venus (and other ERB heroes).

My college degree was in art (equivalent of both a major and a minor before I graduated), which included an appreciation for architecture and ancient art history through archaeology. I also took writing classes and classes on popular literature (was considering an English minor at the time, but it focused on becoming an English teacher, not a writer).

As far as design goes, I began with thematic ideas and then made maps that seemed interesting to me. The contents of the maps were often created well after the map was laid out.

Some themes were pervasive in my maps:

* Make play spaces where the layout and design of the encounter areas affected play (not just geometric shapes on a map).

* Allow multiple paths through a play area

* Fill them with interesting characters, not just hit points with names, abilities, and attack values.

* Create a sense of organic development of an area. Rarely were large architectural projects designed and completed by one creator. They tended to grow piecemeal over time, changing in style, or function, as needed by those who occupied them at the time.

* Buildings (and other spaces) tend to be repurposed over time if they are occupied long enough and not destroyed by calamity of man or nature.

* Create settings for stories without plot or main characters, not the stories themselves. Suggest what might happen, but understand that RP gaming is about letting players create the stories about their characters, not forcing them through the GM’s storylines.

Obviously some of that may not have been in the forefront of my mind at the time. I simply did what felt natural to me. Others have analyzed my work and defined some of what I did. Other insights have come over a lifetime of making play spaces … yet were still present in those early works.

I can point you at a three-part blog post written by Justin Alexander several years ago called Jaquaying the Dungeon (it should be “Jaquaysing the Dungeon” but I quibble). He refers to me by the name I wrote the books under.

–link removed–

Best of success to you on your workshop.

Jennell Jaquays